Now I am able to relate a Series of Most Fortunate Events. You have heard tell of the mythical Nose Museum; you have heard of Secret and Not-So-Secret Nonsense Societies; you have heard of delinquent doctoral dissertations; you have heard of Shakespeare’s freewheeling Falstaff; you have heard of the ascetic and hirsute Indian holy man; you have heard of fiddle-de-dee, the ridicule of the French, and plaster of Paris… Well, you know what I herd?

Now I am able to relate a Series of Most Fortunate Events. You have heard tell of the mythical Nose Museum; you have heard of Secret and Not-So-Secret Nonsense Societies; you have heard of delinquent doctoral dissertations; you have heard of Shakespeare’s freewheeling Falstaff; you have heard of the ascetic and hirsute Indian holy man; you have heard of fiddle-de-dee, the ridicule of the French, and plaster of Paris… Well, you know what I herd?Sheep.

Little could I have imagined that all of these components might combine together in my tour of the University of Lund, in Sweden, conducted by the esteemed Frederick Tersmeden, historian, archivist at the University, and ex-curator of the Student Museum and Archive. Björn and I met Frederick in the heart of the University grounds, where I had probably already trod upon one of the main sites I was about to see. We were here to take something perhaps never asked for nor given at the University, something banned by student guides, anathema to prospective parents, and only dreamt of in your philosophy—that is, a tour of the University’s nonsense.

We began with a survey of some of the more significant sculptures that had been erected in the last hundred years at the University by a special Society, a group dedicated to hokum and hobgoblinry, called Uarda Akademien. We walked the cobbled path, beneath aged trees, to a crossroads of sorts and stood in the center.

There, Frederick told me, on 29 April, 1984 a historic event took place. On this very spot, a massive tent had been erected, a crowd gathered, and a Society put on its very best, to introduce to Lund and the World its latest addition to the history of modern sculpture. Beneath the tent, a curtained area was revealed, housing the sacred site. When the curtains were drawn, there stood a smaller structure of opaque muslin, within which another set of shades guarded the secret sculpture. Having pulled these back, a smaller draped lattice revealed itself, under which stood, the last covered frame finally having been removed, nothing. Nothing stood, but there, at the center of the area previously curtained and muslined, shaded and draped and covered, a small plaque had replaced one of the cobbles in the walk.

There, Frederick told me, on 29 April, 1984 a historic event took place. On this very spot, a massive tent had been erected, a crowd gathered, and a Society put on its very best, to introduce to Lund and the World its latest addition to the history of modern sculpture. Beneath the tent, a curtained area was revealed, housing the sacred site. When the curtains were drawn, there stood a smaller structure of opaque muslin, within which another set of shades guarded the secret sculpture. Having pulled these back, a smaller draped lattice revealed itself, under which stood, the last covered frame finally having been removed, nothing. Nothing stood, but there, at the center of the area previously curtained and muslined, shaded and draped and covered, a small plaque had replaced one of the cobbles in the walk.

It reads, “Here stands a sculpture of nothing.” I can’t say what the reaction of the crowd might have been, but such an ontological sculptural and spatial conundrum could evoke no less than awe. The value of this sculpture was such that, three years later, “nothing” was stolen, and the plaque above the original marks this sad event.

Since we had probed the concepts of space and being, the next stop on our nonsense tour was at a marker of time. It seems that, long ago before the invention of the digital watch, students had no independent way of knowing when to be at their classes on time. They had to listen to the clock tower chime the hour, after which they would have 15 minutes to get to class. Thus, a 10:00 class was actually a 10:15 class, an 11:00 class was not an 11:00 class but at 11:15, etc.. Even after we were ushered into the Age of Civilization with the Digital Watch, the tradition at the University of shifting time 15 minutes into the future continued, to the pleasure of snooze-slapping sluggards everywhere. In order to note this distinctive feature, and to mark exact spot where it must be true in a celestial, astrological sense, members of the Society erected a meridian marker one hour and fifteen minutes in advance of Greenwich Mean Time.

Note bene: to all those at Berklee College of Music, this should sound familiar, for we have been doing such gymnastics of time for many years… that is, until just this semester, when such time-warping turpitude has been discontinued. Berklee, of course, having been founded considerably after the Age of the Digital Watch, has had nothing to blame except that, man, we’re, like, musicians.

Our next stop involved a particularly Swedish concept: that of the lagom. In Swedish, a lagom is the exact right amount, whatever that amount might be in the mind of the speaker. One could have a lagom of sauz on one’s meatball (if one delights in sauz), or a lagom of humor at a ferret’s last rights; whatever the case, it is the “right amount.” Members of the Society decided in 1992 that they should settle the matter of how much, exactly, a lagom was, and the following sculpture demonstrates their intensive research and striking technical precision. Witness the area described by the half circle: ONE (1) carefully calibrated lagom (lgm). Now the world knows.

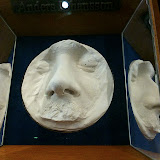

There is one more monument to describe, but it will have to wait until the proper context has been established. On then, to the thing I had been waiting for ever since Björn had described it to me: a visit to the Nose Museum. Yes, the Nasotek, an offshoot of the Esteemed Society, is a museum dedicated to that most upright member of our physiognomy, the nose. Hanging in its hallowed hall are the plaster likenesses of countless noses of various shapes and sizes, belonging to some of the most esteemed students, faculty, and starlets in Sweden. I offer my own nose for consideration:

And a rare honor: a nose captured with its nose. Here is Frederick, posing proudly with his nose.

Click on the photo below for a Picasa gallery of Nasotek shots. Notice that mirrors are set up in each nose box so that one may view the profile.

While the nose likenesses are the centerpiece and pride of the institution, there is much, much more going on. The Nasotek is a full-fledged academic institution, one that publishes a scholarly peer-reviewed journal. It has a Nasologiska fakultenten (Nosology faculty) that, naturally, awards the Doctor of Nosology. Frederick was most generous in gifting me a couple of the journals and two dissertations, one on the nose in heraldry, the other, the nose in music. This latter I shall take back to Berklee College of Music in Boston, put it in a jar with a cottonball soaked in ethyl acetate, laminate in a permanent position of posthumous postulatory perfection a la von Hagens’ “Body Worlds,” and enshrine next to the Stan Getz saxophone in the Berklee library.

The last feature of the Nasotek I shall describe is the final sculpture on the tour, found in the Nasotek itself. Now that you understand the depth of Nasologiska at Lund University, there is one more piece of the context necessary. The following “official” sculpture of the university lies outside in the leafy campus. It is a large block of stone, out of which a man struggles to emerge.

I was told that it might mean some kind of Struggle to escape calcifying Ignorance, or some such snobberdoodle. The Esteemed members of the Nasotek took it upon themselves not only to honor the original, but to honor, above all else, the Nose. In the following indoor (and scaled down) sculpture, you will notice that the block of stone is identical to the sculpture outside.

On the front side, we can see, not Man struggling to break through Ignorance, but the Nose. And only the Nose. Click on the photo to enlarge.

On the front side, we can see, not Man struggling to break through Ignorance, but the Nose. And only the Nose. Click on the photo to enlarge.

And a rare honor: a nose captured with its nose. Here is Frederick, posing proudly with his nose.

Click on the photo below for a Picasa gallery of Nasotek shots. Notice that mirrors are set up in each nose box so that one may view the profile.

|

| Nasotek 8/21/09 |

While the nose likenesses are the centerpiece and pride of the institution, there is much, much more going on. The Nasotek is a full-fledged academic institution, one that publishes a scholarly peer-reviewed journal. It has a Nasologiska fakultenten (Nosology faculty) that, naturally, awards the Doctor of Nosology. Frederick was most generous in gifting me a couple of the journals and two dissertations, one on the nose in heraldry, the other, the nose in music. This latter I shall take back to Berklee College of Music in Boston, put it in a jar with a cottonball soaked in ethyl acetate, laminate in a permanent position of posthumous postulatory perfection a la von Hagens’ “Body Worlds,” and enshrine next to the Stan Getz saxophone in the Berklee library.

The last feature of the Nasotek I shall describe is the final sculpture on the tour, found in the Nasotek itself. Now that you understand the depth of Nasologiska at Lund University, there is one more piece of the context necessary. The following “official” sculpture of the university lies outside in the leafy campus. It is a large block of stone, out of which a man struggles to emerge.

I was told that it might mean some kind of Struggle to escape calcifying Ignorance, or some such snobberdoodle. The Esteemed members of the Nasotek took it upon themselves not only to honor the original, but to honor, above all else, the Nose. In the following indoor (and scaled down) sculpture, you will notice that the block of stone is identical to the sculpture outside.

On the front side, we can see, not Man struggling to break through Ignorance, but the Nose. And only the Nose. Click on the photo to enlarge.

On the front side, we can see, not Man struggling to break through Ignorance, but the Nose. And only the Nose. Click on the photo to enlarge. Because, it seems, that the man here has not quite made it as far through the stone as in the original, a certain fundamental part of him remains, revealed on the back side of the block.

I can only applaud the Nasotek for such an accomplishment, but the credit goes not only to them (and here, oh American University Administrations, take note!): I learned from Frederick that the importance of levity and humor within learning has actually been written into the mission of the University—that these statues are all sanctioned, nay, encouraged, that these and other nonsensical societies are a part of the institutional warp and weft, according to the University’s educational philosophy. Amazing.

The last leg of this tour took us to the Museum of Student Life, which had at one time been curated by Frederick. It is a storehouse of everything non-academic related to student life—the gags and photos, dramatic production scripts, notable clothing, props, and other ephemera, all pieces that probably would have been lost long ago if not for the museum. We saw various curiosities, including medals (which, in a way, mock the frequent bestowing of medals in Swedish culture), jerseys, statues, artwork, and other pieces, many of which came about because of the big festival/carnival that occurs every four years, full of pranks and carnivalesque nonsense. Of particular interest to us, however, was the material stored here authored by Axel Wallengren, otherwise known by his pseudonym, Falstaff, Fakir (the latter word being his “title”), one of the grandfathers of Swedish nonsense, and a Lund University student in the late nineteenth century. Frederick brought out a dusty box, and Björn and I had the privilege of looking through the original documents by the young nonsense artist. One notable document was titled “Lund Just Nu!” and is a parody of the Paris World’s Fair pamphlet. It has much nonsense in it, and Frederick used it as an example of how nonsense, even parodic nonsense, has a life well beyond parody (even though, it may be argued, all nonsense has some parodic tendencies). It is still funny today, even if we are not familiar with the original, parodied text about Paris—a sure sign of nonsense. Of course, Falstaff, Fakir’s text in some ways follows the model closely and has many inside jokes, but the humor and literary value hold because the parody goes beyond parody to nonsense.

The last leg of this tour took us to the Museum of Student Life, which had at one time been curated by Frederick. It is a storehouse of everything non-academic related to student life—the gags and photos, dramatic production scripts, notable clothing, props, and other ephemera, all pieces that probably would have been lost long ago if not for the museum. We saw various curiosities, including medals (which, in a way, mock the frequent bestowing of medals in Swedish culture), jerseys, statues, artwork, and other pieces, many of which came about because of the big festival/carnival that occurs every four years, full of pranks and carnivalesque nonsense. Of particular interest to us, however, was the material stored here authored by Axel Wallengren, otherwise known by his pseudonym, Falstaff, Fakir (the latter word being his “title”), one of the grandfathers of Swedish nonsense, and a Lund University student in the late nineteenth century. Frederick brought out a dusty box, and Björn and I had the privilege of looking through the original documents by the young nonsense artist. One notable document was titled “Lund Just Nu!” and is a parody of the Paris World’s Fair pamphlet. It has much nonsense in it, and Frederick used it as an example of how nonsense, even parodic nonsense, has a life well beyond parody (even though, it may be argued, all nonsense has some parodic tendencies). It is still funny today, even if we are not familiar with the original, parodied text about Paris—a sure sign of nonsense. Of course, Falstaff, Fakir’s text in some ways follows the model closely and has many inside jokes, but the humor and literary value hold because the parody goes beyond parody to nonsense.

Frederick agreed to read a particularly nonsensical passage from one of Falstaff, Fakir’s books, How to be a Scholar. In the first film, Frederick reads a parody of a schoolbook example of German phrases to be translated. You don’t need to know German to hear some of the nonsense and humor, but German speakers will find this especially good. The second film has the Swedish translation—which is completely nonsensical. (Note: If you look closely at these films, you should see in the upper right hand corner, a small statue that looks suspiciously like Frederick himself.)

Frederick introduced some other Lund University nonsensites, with their own pamphlets and ephemera, until we were up to our kippers in nonsense, but eventually we had to leave, took lunch at a beautiful old hotel nearby, famous for being a University institution, and took our leave back to Malmö. It’s hard to describe what an extraordinary tour this was, but I hope the length, at least, of this entry, begins to do so!

I was talking at a later point to a Finnish fellow, and when I mentioned Swedish nonsense he looked askance, but when I added some details about the University of Lund, he retreated, saying, “Oh, well of course in Lund such things may be so…”

Many thanks to Frederick (with whom, indeed, I have an affinity), and to Björn for setting this up.

Frederick introduced some other Lund University nonsensites, with their own pamphlets and ephemera, until we were up to our kippers in nonsense, but eventually we had to leave, took lunch at a beautiful old hotel nearby, famous for being a University institution, and took our leave back to Malmö. It’s hard to describe what an extraordinary tour this was, but I hope the length, at least, of this entry, begins to do so!

I was talking at a later point to a Finnish fellow, and when I mentioned Swedish nonsense he looked askance, but when I added some details about the University of Lund, he retreated, saying, “Oh, well of course in Lund such things may be so…”

Many thanks to Frederick (with whom, indeed, I have an affinity), and to Björn for setting this up.

No comments:

Post a Comment